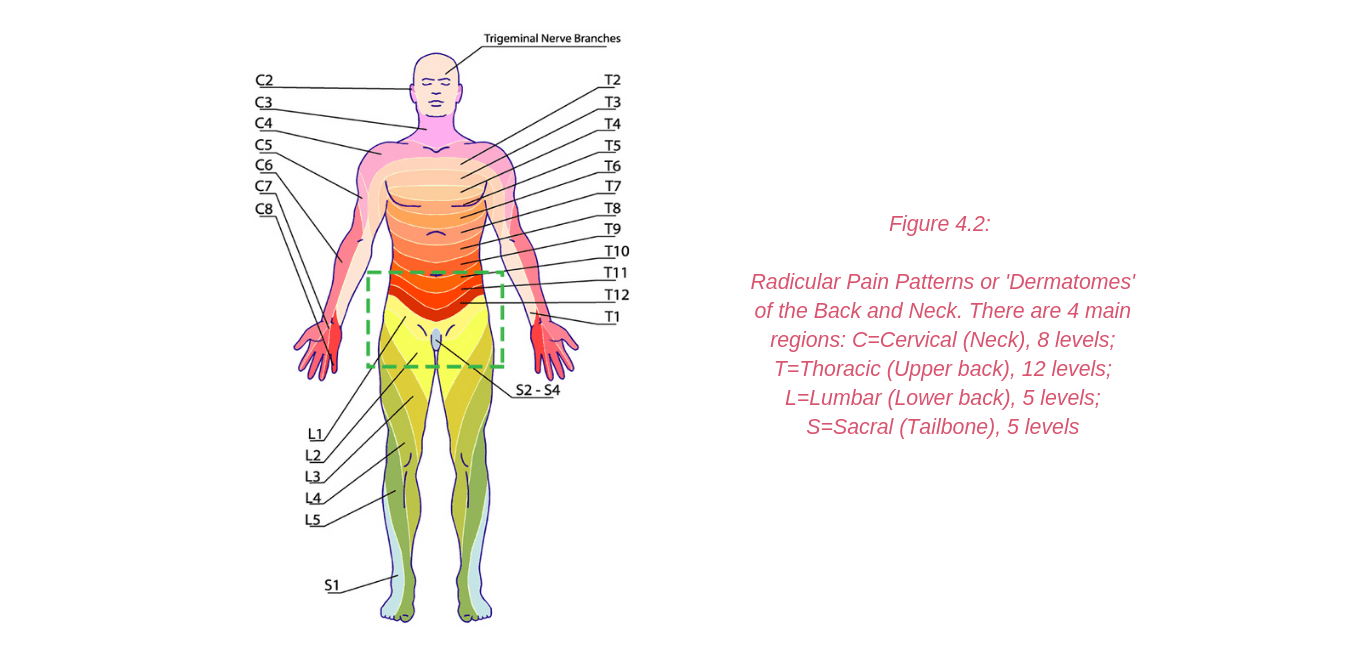

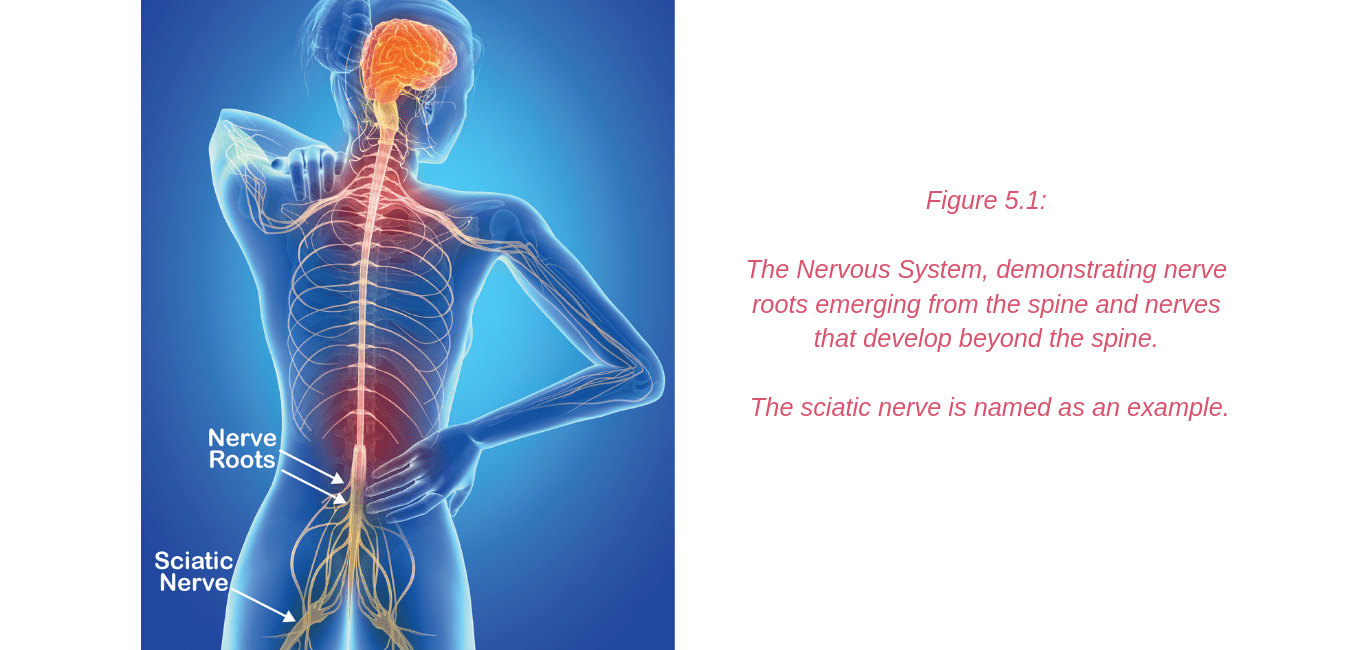

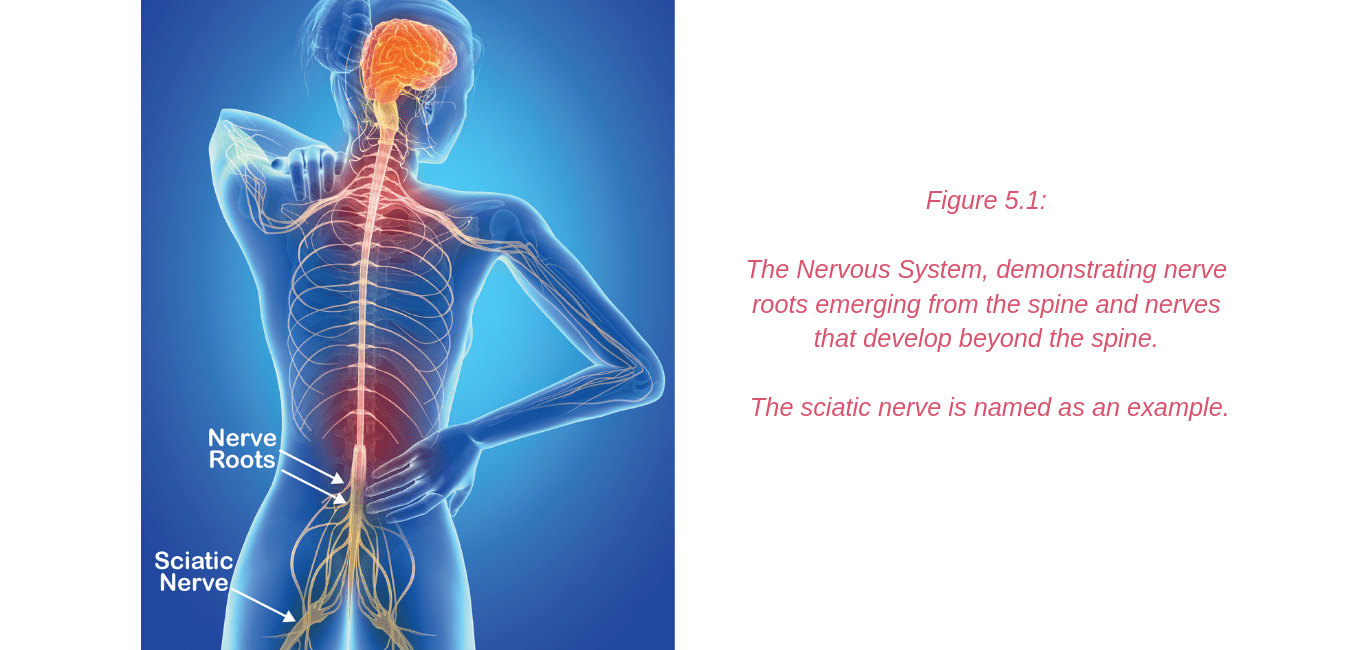

The nervous system (Figure 5.1) is a complex network of nerves and cells that carry messages between the brain and spinal cord and your body. It is through this system that we feel, move and control our bodily functions. Nerve roots leave the spinal cord via the intervertebral foramina (holes or spaces between the vertebrae) and join together from various levels of the spine to travel as cord-like structures, called nerves, to their destinations. It is these nerves that travel outside the spinal cord that are referred to as “peripheral nerves”. Some peripheral nerves travel only a short distance and others all the way from the lower back to the foot. Along their journey they run between and through muscles and fibrous tunnels. While radicular pain arises from a problem as the nerve root exits the spine, nerve-related pain may develop due to a problem along the pathway of a peripheral nerve, outside the spine. Pain related to a nerve is called “Neuralgia”.

Neuralgia felt around the hip and pelvis may develop in many ways including excessive compression or stretch of the nerve. This may be caused by a sudden, acute mechanism, for example a fall or blow to the area resulting in compression, or the leg being caught and wrenched, resulting in stretch. Alternatively, the onset may be subtle, with a gradual onset associated with sustained postures or repetitive movements that cause cumulative nerve irritation. Nerves will also be influenced by the health of the tissues they run through or alongside. For example, high muscle tension or tendinopathy may over time result in irritation of neighbouring nerves.

Nerve related symptoms are usually experienced differently from pain associated with muscle and joint problems.

Peripheral nerve irritability may result in:

- symptoms in the area served by that peripheral nerve (which is different from dermatomal patterns associated with nerve root irritation -radicular pain)

- burning pain

- odd zings or zaps of pain

- tingly sensations or numbness

- weakness – only for those nerves that supply muscles, like the femoral nerve

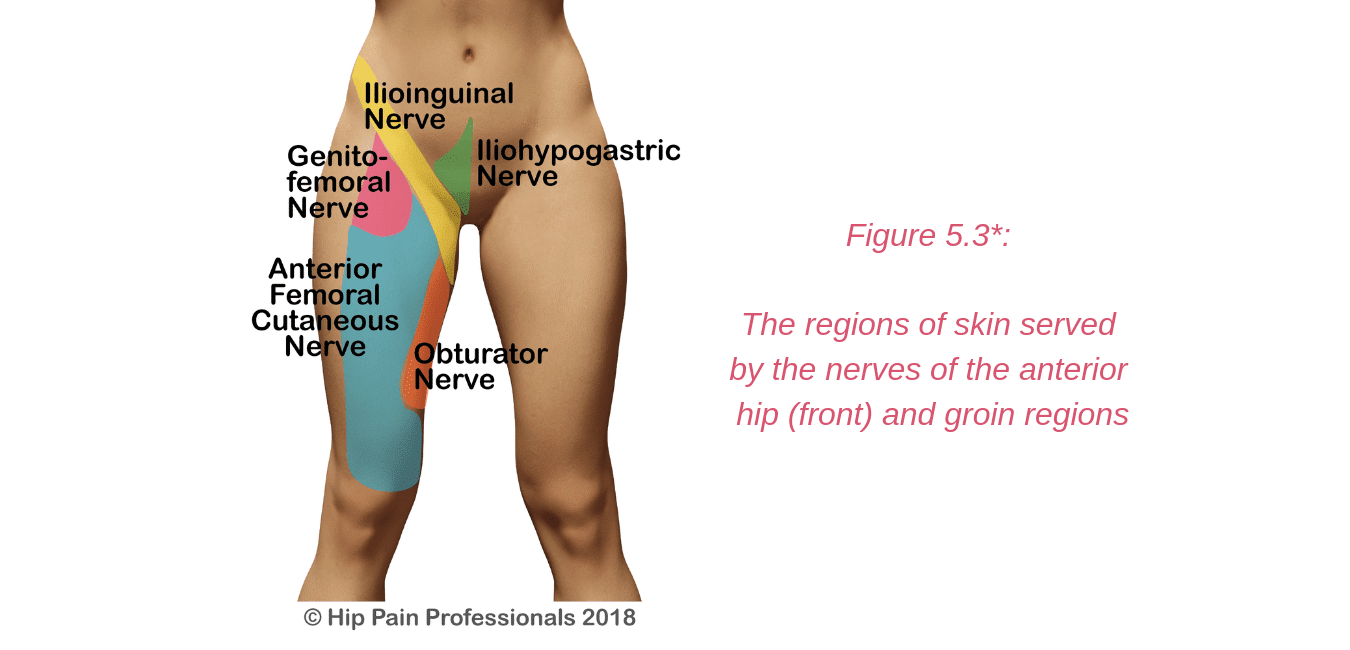

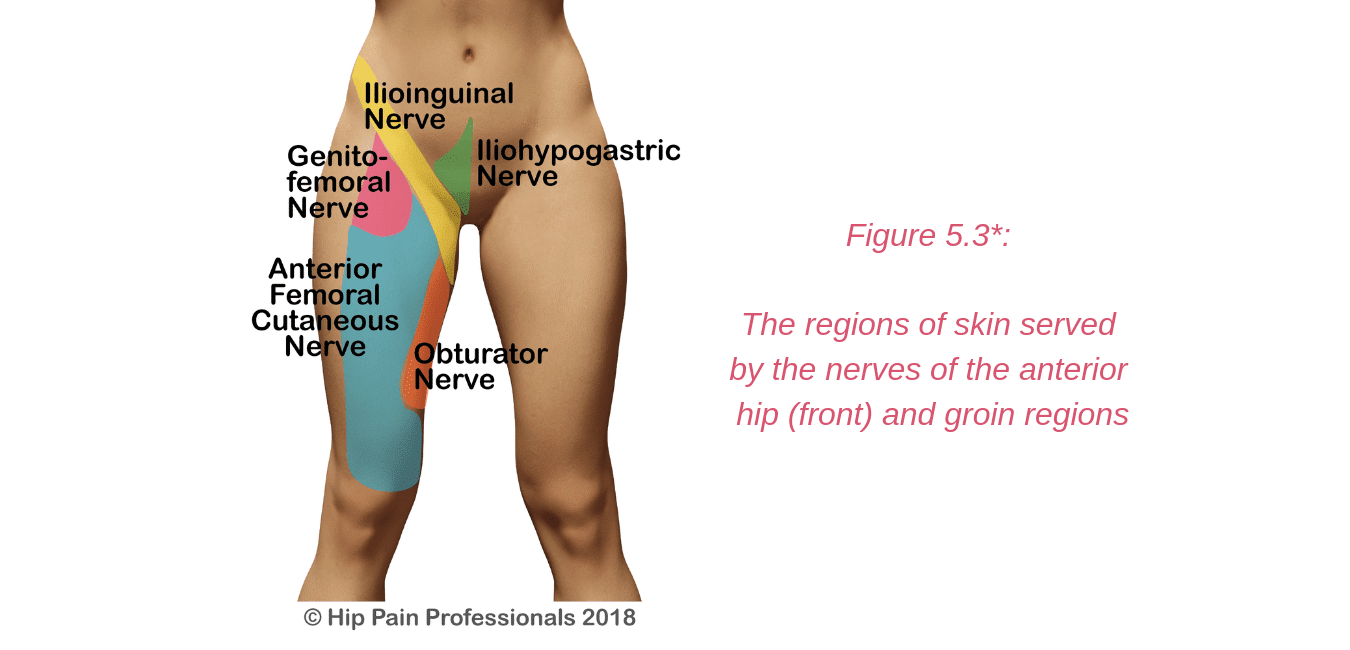

In viewing the individual nerves that may be contributing to your anterior hip pain, be aware that some nerves may cross through and supply more than one region. Additionally, some areas of skin may have several nerves that serve the area. This sometimes makes accurate diagnosis tricky. Your hip pain professional will help to identify the cause of your pain.

Nerves of the Anterior Hip and Groin Regions:

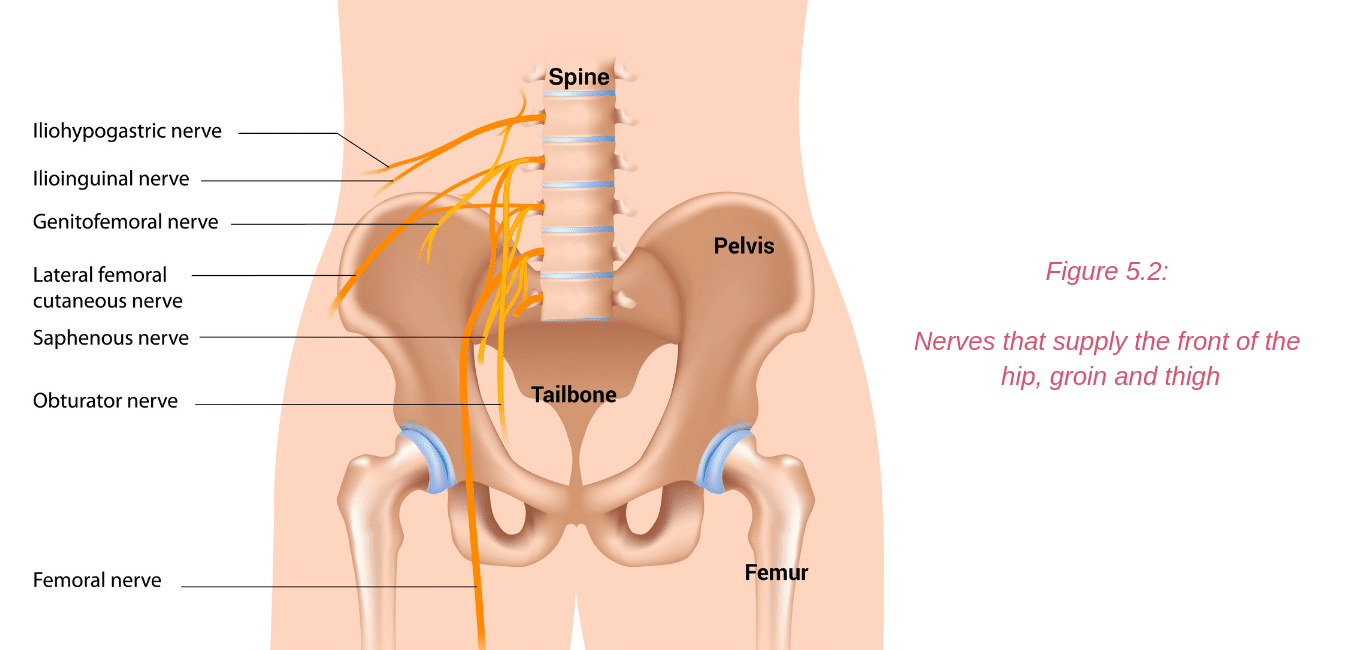

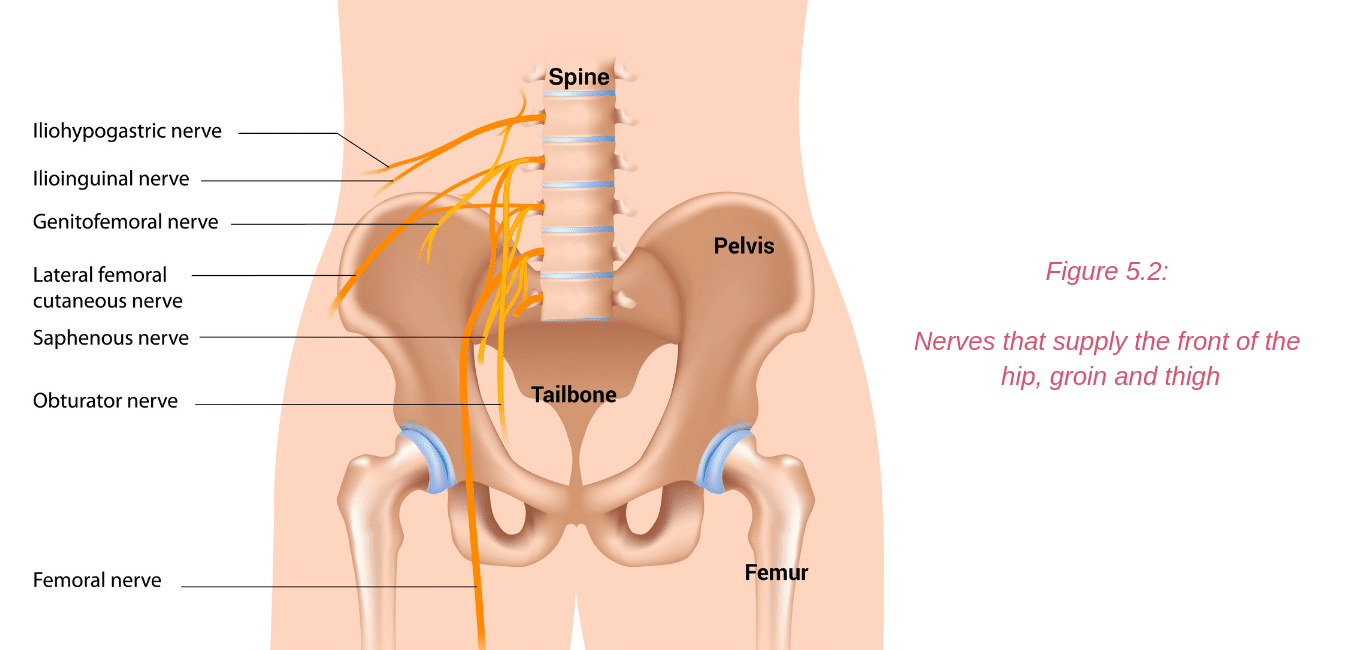

Nerves that supply the front of the hip, groin and thigh (Figure 5.2) include:

- the iliohypogastric nerve

- the ilioinguinal nerve

- the genitofemoral nerve

- the obturator nerve

- the femoral nerve: the anterior femoral cutaneous nerve

Nerve Related Pain/Neuralgia in the Anterior Hip & Groin Regions

Irritation or damage to the ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric and genitofemoral nerves may occur as they travel through the muscles of the back and abdomen. Most commonly, symptoms may arise following some sort of abdominal or groin surgery, such as hernia repair. The nerves may be damaged at the time of surgery or become entrapped in the scar tissue or mesh used for hernia repair. Endometriosis may also sometimes affect these nerves. The symptoms are usually pain, with or without tingling or numbness in the area of nerve supply (Figure 5.3). The iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves also provide some motor supply (the ability to make the muscles contract and work) to the abdominal muscles, so there may be some weakness of the abdominals experienced in conjunction with the nerve irritation.

Irritation or damage to the ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric and genitofemoral nerves may occur as they travel through the muscles of the back and abdomen. Most commonly, symptoms may arise following some sort of abdominal or groin surgery, such as hernia repair. The nerves may be damaged at the time of surgery or become entrapped in the scar tissue or mesh used for hernia repair. Endometriosis may also sometimes affect these nerves. The symptoms are usually pain, with or without tingling or numbness in the area of nerve supply (Figure 5.3). The iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves also provide some motor supply (the ability to make the muscles contract and work) to the abdominal muscles, so there may be some weakness of the abdominals experienced in conjunction with the nerve irritation.

For Pain Related to Nerves/Neuralgia of the Anterior Hip:

- Perform specific tests in the clinic to see if nerve involvement is likely

- Provide treatments and give you exercises that may improve the health or movement of the nerve

- Help improve health of the muscles and tendons beside the nerve (this may be the source of nerve irritation)

- Review the position you spend time in and activities you perform daily and provide strategies when performing these tasks that might help protect the nerve, thus reducing your symptoms. This may include changing your sitting or lying posture, or changing stretches or strength exercises that you have been performing that may be contributing to the irritation the nerve

- Provide nerve gliding or mobility exercises that can be useful in some situations

- Refer you for further tests or to a neurologist, orthopaedic specialist or other pain specialist if required.

- In some cases, your hip pain professional may refer you to a pelvic floor physio for further assessment should they consider the pelvic floor muscles are involved.

* Please note: Nerve supply can overlap and be quite variable between individuals. The diagram provided in this section provides an approximate guide only of the nerve supply in this region.

Joint Related

Joint Related  Soft Tissue Related

Soft Tissue Related  Bone Related

Bone Related  Back Related

Back Related  Peripheral Nerve

Peripheral Nerve  Other causes

Other causes